To my mind, argumentation studies doesn’t pay enough attention to the psycho-economics (and the just plain economics) of argumentation. How much, for example, does it cost you to engage (or not engage) in an argument with someone? How much do you have invested in your beliefs? What will it cost you in time, Â money, and shame to change them? There’s a cost to everything.

One of the costs that comes with believing (or maybe just being) is stress. Yesterday there was an op-ed on point in the NYT by Lisa Feldman Barrett of Northeastern (Boston). She writes:

But scientifically speaking, it’s not that simple. Words can have a powerful effect on your nervous system. Certain types of adversity, even those involving no physical contact, can make you sick, alter your brain — even kill neurons — and shorten your life.

Your body’s immune system includes little proteins called proinflammatory cytokines that cause inflammation when you’re physically injured. Under certain conditions, however, these cytokines themselves can cause physical illness. What are those conditions? One of them is chronic stress.

Your body also contains little packets of genetic material that sit on the ends of your chromosomes. They’re called telomeres. Each time your cells divide, their telomeres get a little shorter, and when they become too short, you die. This is normal aging. But guess what else shrinks your telomeres? Chronic stress.

If words can cause stress, and if prolonged stress can cause physical harm, then it seems that speech — at least certain types of speech — can be a form of violence. But which types?

That last question is a critical one. Barrett’s answer seems to depend on the duration of the stress caused by the speech:

That’s also true of a political climate in which groups of people endlessly hurl hateful words at one another, and of rampant bullying in school or on social media. A culture of constant, casual brutality is toxic to the body, and we suffer for it.

Here’s the payoff:

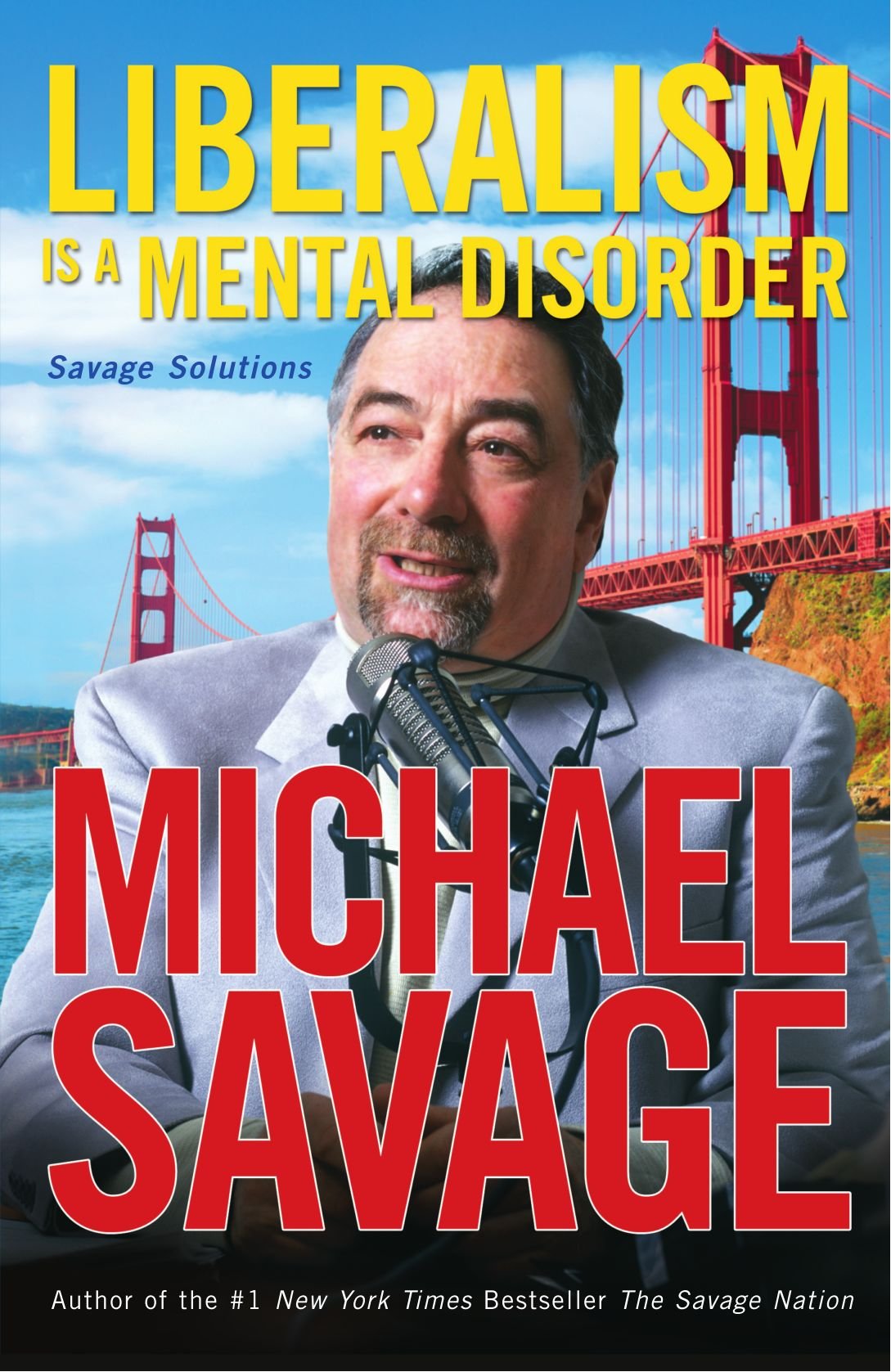

That’s why it’s reasonable, scientifically speaking, not to allow a provocateur and hatemonger like Milo Yiannopoulos to speak at your school. He is part of something noxious, a campaign of abuse. There is nothing to be gained from debating him, for debate is not what he is offering.

Well, there’s the problem. In the first place, to Milo’s many adoring fans, he’s not abusing anyone. If anything, he’s got to put up with your abuse (as they frequently allege). Besides, they might claim they get a rush of pleasure from the truth he speaks and that the discomfort people feel is the pain of cognitive dissonance. Â Second, there’s an easy to way to avoid Milo’s noxious message: don’t go to his talk.

I’m sympathetic to the idea that there’s a psychological cost to unwelcome ideas. I’m also sympathetic to taking that into account as we offer them. But it’s difficult to see how these two things yield banning Milo. That his beliefs impose a high cost on hearers doesn’t seem sufficient to ban or even avoid them. I’ll leave it to the reader as an exercise to come up with counterexamples to Barrett’s view.