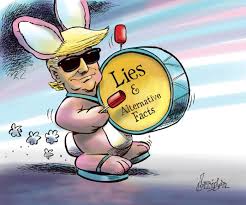

Kellyanne Conway has had a hard couple weeks. She had the ‘alternate facts‘ brouhaha, then she had the case where she made up a massacre in Bowling Green.  That then yielded a refusal by a number of news outlets to interview her. CNN’s ran for 48 hours. She had a credibility deficit.

Kellyanne Conway has had a hard couple weeks. She had the ‘alternate facts‘ brouhaha, then she had the case where she made up a massacre in Bowling Green.  That then yielded a refusal by a number of news outlets to interview her. CNN’s ran for 48 hours. She had a credibility deficit.

Jonah Goldberg, over at National Review Online has come to Conway’s defense saying that she is “good at her job, and the media hates her for it.” You see, she’s regularly been sent on a tough mission – to defend Trump’s policies against a media set on interpreting everything they say in the worst possible light.

President Trump’s surrogates, including Vice President Mike Pence, have mastered the art of defending straw-man positions that don’t reflect the actions and views of the president himself.

Just for clarity’s sake, it’s worth noting that I don’t think Goldberg is holding that Conway must defend straw man positions, but rather she must defend against straw men of her positions. It has been a bit of a pet peeve of mine to see the language of informal logic abused, but this one is a doozy! Regardless, the point is a fair one. If folks have been getting the views and policies wrong, it’s the job of the communicators to set the record straight.

But it’s here that Goldberg switches gears – you see, if you must defend against those who straw man in hostile fashion, then you, too, must fight dirty. And a lesson from history is a case in point.

In 2012, Susan Rice, Barack Obama’s national-security adviser, flatly lied on five Sunday news shows, saying that the attack on the Benghazi compound was “spontaneous†and the direct result of a “heinous and offensive video.†No one talked of banning her from the airwaves. Nor should they have. Here’s a news flash for the news industry: Birds are gonna fly, fish are gonna swim, and politicians are gonna lie.

This, of course, is a curious line of argument, since the lies made the administration’s position (in both cases!)look considerably worse. Who needs a straw manner in one’s opposition when one is doing such a bang-up job oneself?