I’ve been wondering for a while about what exactly gets shown with tu quoque arguments. Is it that the premise is false, or no longer justified? Since it’s an ad hominem form of the argument, perhaps it is more just a case against the people speaking, perhaps that they don’t understand their own case or aren’t sincere. Or is it that they have a double standard. I think that, depending on the setup, these are all on the table. Though the last one, the attack on the ethos of the speaker on the other side using a double standard is the most likely and most argumentatively plausible.

Here’s why. When we charge tu quoque, it’s often a culmination of a series of argumentative exchanges. Sometimes over years. What we’ve got then is a lot of evidence about the person’s argumentative and intellectual character. The tu quoque is a kind of caught-red-handed moment you serve up to show that the person’s not an honest arbiter of critical standards. That they play fast and loose, and always to their own advantage, with evidence, degrees of scrutiny, and what’s outrageous or not.

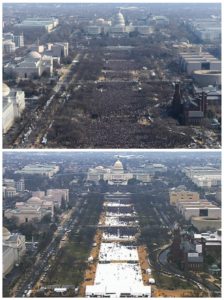

Amanda Terkel at Huffpost, with “Trump Administration Absolutely Outraged Someone would try to Delegitimize a President” has an interesting tu quoque with the Republicans about the recent accusations that the current President isn’t legitimate. Take, for example, John Lewis saying, in response to the challenge that The Russians had interfered with the election:

I do not see Trump as a Legitimate President.

The result was that the Republicans responded pretty harshly (including Trump’s tweet). But then they complained about the negativity in the media about the Presidency, and Reince Priebus (ex-RNC Chair, now Trump’s Chief of Staff) complained that

There’s an obsession by the media to delegitimize this president, and we are not going to sit around and let it happen. . . .You didn’t have Republicans questioning whether or not Obama legitimately beat John McCain in 2008

But wait, Amanda Terkel points out. Trump very famously was a birther. And so had been on a years-long de-legitimating campaign.

So what follows? A regular phenomenon with tu quoque arguments is that pointing out the hypocrisy is the end of the game. No conclusions are offered, and so it goes with the Terkel piece.

Again, my thoughts have been that a conclusion about the target proposition very rarely can be supported by the tu quoque, but some cases are relevant to the issue. Again, if the challenge is to the sincerity or the intellectual honesty of a speaker, especially with double-standards, there are conclusions we can draw. But does the fact that it’s politics make it worse or better?