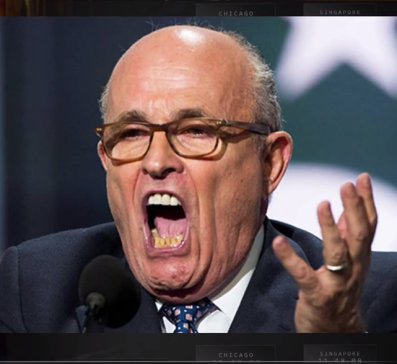

Yesterday it seemed to me that Rudy Giuliani was not doing the standard relativist argument, but, more ominously for our democratic institutions, was (incoherently) challenging the adversarial process for settling questions of fact.

The initial relativism of factual claims is the condition of the adversarial legal system. Someone says x, someone says y, and an impartial judge listens to their arguments and makes a factual determination. The presupposition is that both cannot be correct.

Giuliani seemed to be arguing that because of the disagreement over the factual claims at issue in this case, no resolution is possible, and so any result at all is bound to be unjust to one of the parties. Naturally, this view itself favors one of the parties (conveniently, his).

Today, however, it seems he’s just about to go full relativism, but only with regard to certain questions.

Consider the following exchange from an interview with Fox News:

MacCallum: What did you mean by that?

Giuliani: Oh, very simple. I’m talking about in this particular situation, one person says the Flynn conversation took place. The other person says the Flynn conversation didn’t take place. What’s the truth? You tell me how you figure out the truth.Â

MacCallum: Well either it did or it didn’t.

Giuliani: It’s like the tree falling in the forest. Did anybody hear it? I mean how do we know what the truth is? Â

MacCallum: You’re talking about whether or not the president asked James Comey to go easy on Michael Flynn. And James Comey says he did, and the president says he didn’t.

Giuliani: That’s right and they will possibly charge him with perjury should he give that answer. That’s why I’m saying in situations like this, to prosecutors, the truth is relative and it’s not absolute like some philosophical concept.

Unlike the tree case, there were observers to whatever conversation we’re talking about–namely, the participants. So points off Giuliani for not noticing that.

Now again it seems to me that the law does have a system for handling cases of, what to call them, extreme factual disagreement–a trial. If it is the case, as Giuliani alleges, that nothing can be known for certain, then there’s a default setting (to the defense).

So Giuliani again balks at embracing full-throated relativism. He’s only a relativist when it’s convenient.