A few months back, Rob Talisse and I introduced the notion of spitballing. Here’s the rough version of how the notion works:

A few months back, Rob Talisse and I introduced the notion of spitballing. Here’s the rough version of how the notion works:

At its core, spitballing works as follows: One makes multiple contributions to a discussion, often as fast as one can think them up (and certainly faster than one can think them through). Some contributions may be insightful, others less so, but all are overtly provocative. What is most important, though, is that each installment express a single, self-contained thought. Accordingly, slogans are the spitballer’s dialectical currency. As the metaphor of the spitball goes, one keeps tossing until something sticks; hence it helps if one’s slogans are tinged with something disagreeable or slightly beyond the pale. As the spitballer’s interlocutors attempt to reply to what he has said, the spitballer resolutely continues spitballing.

If the spitballer must answer for an inaccurate or otherwise objectionable contribution, crying foul that others don’t interpret their statements properly is the default strategy:

Accordingly, when a spitballer’s pronouncement is subjected to critical analysis in, say, print media, the spitballer’s response is simply to return to the confines of the television studio to denounce the interpretation of the slogan that was scrutinized. The denouncement begins with an indignant “what I actually said was . . .” and is followed with the introduction of a new slogan –hence a new provocation – which is no more precise or transparent than the original. Thus the process begins anew.

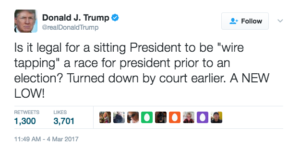

Our target for the original posting was then candidate Trump, and now it’s President Trump. The new developments with the investigations of Trump’s wiretapping tweets have exactly the form of sptiball-then-ironman from before. First, the spitballs

OK, and then the next day, plenty of folks (including FBI director James Comey) come out to say these claims are unsubstantiated. Then Kellyanne Conway suggested that it’s possible to surveil through TV sets and microwaves. Sean Spicer then clarified some of the tweets noting that (at least in two of them) ‘wiretapping’ is in quote marks, which means that it really stands for… general surveillance. And presumably ‘Trump Tower’ means the Trump Campaign and its representatives.  And by ‘President Obama,’ he really means someone in a government agency. And now that House Intelligence Committee Chairman, Devin Nunes (R-CA) has announced that athere is evidence that there was information collected incidentally and widely disseminated among the intelligence community, there is the sense that the Trump claim has been vindicated.

First, consider Trump himself. In the “Is Truth Dead?” Time Magazine interview, Trump, in responding to the question about the tweets and their troubles, responds:

When I said wiretapping, it was in quotes. Because a wiretapping is, you know today it is different than wire tapping. It is just a good description. But wiretapping was in quotes. What I’m talking about is surveillance. And today, [House Intelligence Committee Chairman] Devin Nunes just had a news conference.. . . That means surveillance and various other things.

Note, however, that in one, ‘wiretapping’ was not in quotes. But, hey, when it’s Twitter, maybe nuance is lost. Wait…

The iron-manning move went into full swing afterwards, which turned not just to the re-interpretation strategy, but to the “if this accusation has anything to which it could be applied, then it’s really important” move. And so, Johnathan Turley, at The Hill:

Of course, the original tweets were poorly worded and inappropriate as a way for a president to raise this issue. Moreover, the inadvertent surveillance is rightfully distinguished from the original suggestion of a targeting of Trump. However, this would still be a very serious matter if intelligence officials acted to unmask the names and distribute them.

And the point of spitballing is made — one makes whatever accusation against the opposition one wants. Then these accusations are reinterpreted to fit the evidence and made to be more alarm bells about possibilities of really bad things.